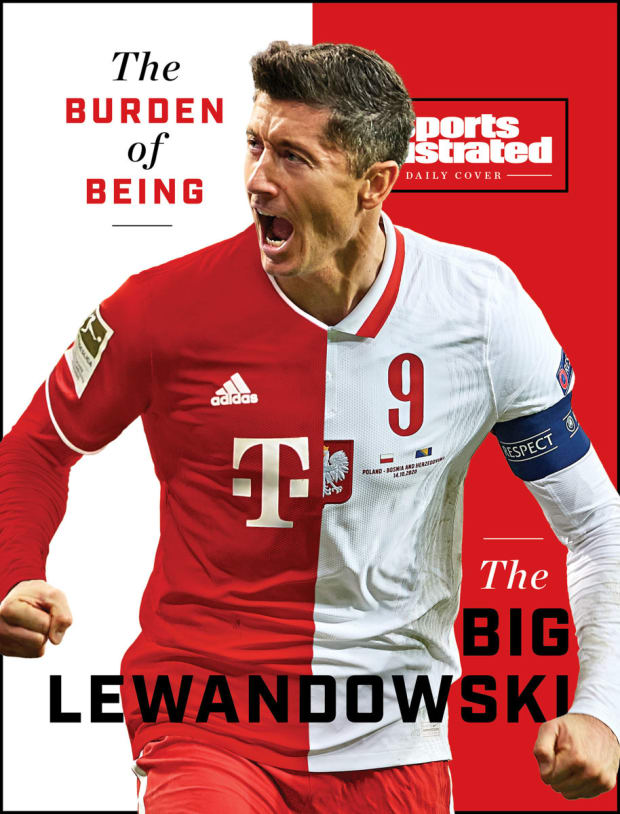

Robert Lewandowski has become the world's top player at Bayern Munich, which has Poland back on the map and thinking big—perhaps to a fault.

It certainly didn’t feel like destiny or determinism at the time. If anything, it felt like Robert Lewandowski’s world was falling apart around him, like his dreams were being yanked out by the roots.

He was 17. A year earlier, in 2005, his beloved father Krzysztof had died after a lengthy bout with cancer. Absent his mentor and confidant, Robert forged ahead with football anyway and reached the reserve team of Legia Warsaw, the biggest club in the Polish capital. But injuries derailed him and after a season, he was let go. His slight frame likely wouldn’t adapt to the rigors of the pro game, Legia said. And so there was Lewandowski in the summer of 2006, facing a demoralizing crossroads. The only two options were taking a significant and uncomfortable step back, or walking away altogether.

His body wasn’t ready yet, but his heart and mind seemed to be. He persevered, signing with a small team in Poland’s third tier called Znicz Pruszków. Lewandowski led the division in goals in 2006–07 and helped the club earn promotion. He also topped the second division scoring chart the following season. By then, the ascent appeared inexorable and at the start of the 2010–11 campaign, Lewandowski was playing under the bright lights at Borussia Dortmund.

“I had three difficult situations for a young man,” Lewandowski says of his father’s absence, Legia’s rejection and the injury. “But I knew that I had to push. I had to be still believing that I can do something. For sure that was a very difficult time for me. That was like a test, to challenge me. … So I choose this way, this very difficult way, but the way that hopefully it doesn’t matter what they say to me. It’s more important what I believe.”

That spark, the determination to choose the “difficult way,” came from somewhere. It probably helped that Lewandowski’s parents were accomplished athletes and P.E. teachers. Krzysztof was a judoka and soccer player, and Lewandowski’s mother, Iwona, was a pro volleyballer. Sports were a part of the family’s identity. Its origin also might be deeper. This wasn’t destiny. But there was an inclination, an instinct, a resolve on Lewandowski’s part to believe in himself and persevere. Perhaps it was the result of nominative determinism.

Many surnames come from professions, and there’s a fun theory, which gained traction thanks to renowned Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, that surnames also might lead to professions. Someone named Baker could subconsciously gravitate toward baking or working with food, for example, because of the comfort and positive association they have with their name. So nominative determinism could’ve played a role in drawing Usain Bolt to the track, Cecil and Prince Fielder to baseball, or legendary Arsenal manager Arsène Wenger to North London.

Krzysztof and Iwona didn’t want anything to stand in the way of their son’s progress or potential. So they ignored more traditional and complicated Polish names in favor of Robert. It’s simple to pronounce, simple to spell and relatively common around the world.

“My dad told me about the history of my name and he said to me, ‘We chose this name because it’s an international name. We never worry that Robert is anything but Robert,’ ” Lewandowski, now 32, says. “My dad told me that it will be easy for everyone around the world, and that’s why. He said that just for fun. ‘If you will be famous, I want it easy to say because Lewandowski is already a little bit difficult.’ ”

If his first name helped Lewandowski imagine limitless and borderless possibilities, it also may have impacted the way the rest of the world perceived him. And that has helped shape his journey. Poland doesn’t lack soccer pedigree. A generation of talented players bracketed by the likes of Grzegorz Lato and Zbigniew Boniek took the national team to the bronze medal at the 1974 and 1982 World Cups. But as the Iron Curtain fell, as soccer went global and as a tsunami of TV money flooded the leagues and clubs of Western Europe, Poland’s run proved unsustainable. An inferiority complex set in and, according to Lewandowski, that was accompanied by problems of perception.

“If you are from the country like me, from Poland, that is not a big country, or we don’t have so many good players, you are minimum one or two steps behind. I knew that I saw so many walls before me,” he says.

Poles no longer played for the biggest clubs, competed for the biggest trophies or had a role in the increasingly global and connected conversation permeating the game. In the voting for world soccer’s two most prestigious player of the year awards, the Ballon d’Or (launched in 1956) and FIFA’s honor (1991), a Pole hadn’t finished in the top three since Boniek came third in 1982.

“Even if they have off seasons, there’s a bias toward big countries and big players. There’s no two ways about it,” says Janusz Michallik, the Polish-born, former U.S. national team defender who now does TV and radio in both the U.S. and his native land.

But Lewandowski became impossible to ignore.

“He’s been knocking on the door for so long and finally, finally, they have to say, ‘Well, we have to give it to him,’ ” Michallik says.

Lewandowski's early determination became a blueprint, then a habit, then a lifestyle. Extra training, strict discipline, and a monastic devotion to his diet (he earned a bachelor’s degree in physical education and his wife, Anna, is a nutritionist) underpinned a focus and personal professionalism that’s noteworthy even at soccer’s highest level. Lewandowski pursued global renown because it had been innately possible since the beginning—his parents had accounted for his nationality—and the willingness to sacrifice and suffer he developed as a teenager remained as his career took off. He says he now enjoys the work because he’s seen the rewards.

Lewandowski spent four years in Dortmund, won two German championships and led the Bundesliga in goals in 2013–14. The following season, after flirting with Real Madrid, Lewandowski joined Bayern Munich. There, he would set new standards in relentless scoring consistency. From the 2015–16 campaign through 2018–19, Lewandowski tallied at least 40 goals in all competitions, helping Bayern to the league title each season. Then as he turned 31, he somehow reached an even higher level. He became soccer’s most complete finisher, an unstoppable penalty-area presence. Lewandowski scored 55 times in 2019–20, paced Bayern to the UEFA Champions League, Bundesliga and DFB-Pokal treble and “finally, finally,” was named FIFA’s player of the year (the Ballon d’Or wasn’t awarded because of the pandemic). They had to give it to him.

“But even when I won something, sometimes after one title I will want more. Success makes me more hungry for the next trophy,” he says. "After so big a season, also you can think like, O.K., I don’t have to prove anymore—nothing. But it’s not like I can be relaxed, like it can be easy. Now it’s, O.K., I need more.”

And so there was more. Although his untimely injury damaged Bayern’s hopes of a Champions League repeat, Lewandowski made more history in 2020–21 by breaking Germany and Bayern legend Gerd Müller’s

single-season Bundesliga scoring record (Bayern also won an unprecedented ninth straight Bundesliga title and the FIFA Club World Cup). Lewandowski’s total of 41 league goals, reached in only 29 matches, was the highest by far in Europe’s top five domestic circuits. Müller’s venerable mark had stood since 1972—two years before he knocked Poland out of the ’74 World Cup. That made it especially gratifying for the millions of Poles who’d been waiting to see a countryman make his name on the global stage.“Football players, after 30 years, they’re already going down and in my case, it’s a different way,” he says.

Lewandowski has beaten the odds. He validated his parents’ hunch and stands astride the world. He is the most famous Pole alive, and probably would do pretty well compared to those who aren’t.

“Robert Lewandowski is the best ambassador for Poland in the world. Nobody comes even near,” Michallik says before tossing out names like Copernicus and Chopin.

“But with that comes great responsibility.”

This is where Lewandowski’s feel-good story gets complicated. It’s the part where the unintended irony of his name—one meant for the world, not for Poland—comes into focus.

Przemysław Frankowski's parents didn’t give him an easy name. The 26-year-old from Gdańsk is a Polish international who plays his club ball in MLS for the Chicago Fire. His first name is pronounced “Sheh-me-suav,” but his teammates and colleagues just call him Frankie. And when Frankie is hanging out or traveling around Chicagoland, which has one of the largest Polish expat populations in the world, he can’t help but notice the love for Lewandowski.

“I see a lot of people wearing Lewandowski’s jersey, not only from the Polish national team but also from Bayern,” Frankowski says through a translator. “He’s their best player ever and they are very much into him. When I have a meeting with fans here from Chicago, they always want to know how he is, both when he plays and also outside the game. He’s someone who is always on their mind.”

The passion for the Polish national side is fierce. Frankowski says fans are like “wind at our back” inside the stadium. But that energy and ferocity don’t dissipate at the final whistle, and when things go wrong, as they have often over the past few decades, that wind becomes a storm. The Polish press buys into it and helps fuel it, Michallik says.

Lewandowski is Poland’s captain. He is the most-capped player in the country’s history and its leading marksman going away. But that’s not enough. Polish fans are tired of basking in the reflected glory of his accomplishments in Munich. They’re ready for their global superstar to deliver for home soil. It’s not enough that he’s an ambassador. He must become a conqueror. They long for a bygone era that probably can’t be duplicated, and they're desperate to see their Orły—the Eagles—contend at a major tournament. And so Poles pin their hopes, expectations and frustrations on the man they believe can (or should) make it happen. The pressure is enormous, and their love can become toxic.

“Poles can be very vengeful in a way, in their attitude toward the players,” Frankowski says. “Every time something goes wrong in an international cup or some other big tournament, there is a lot of hatred. There is a lot of bad press and people get really nasty about it.”

The quadrennial European Championship kicks off Friday, and Poland begins its run on June 14 as part of a difficult group that includes three-time winner Spain, Sweden and Slovakia. It’ll be Lewandowski’s fourth major international tournament. Euro 2012 was the first and he started strong, scoring in just the 17th minute of his first game, a 1–1 draw with Greece in Warsaw. But Poland, a co-host, finished last in its group. After failing to qualify for the 2014 World Cup, the Eagles enjoyed a surprising run to the Euro 2016 quarterfinals. But Lewandowski tallied just once across five games as defense dominated.

Expectations were soaring ahead of the 2018 World Cup in Russia, Poland’s first since ’06. Lewandowski was in his prime and led all European scorers during qualifying, and a group containing Senegal, Japan and Colombia seemed more than manageable. But disaster struck. Poland lost its first two matches and was eliminated before beating the Japanese in a meaningless first-round finale. Lewandowski was goalless. The team was like a “broken puzzle,” he says.

Never mind the fact that Poland can’t come close to providing the sort of support and service that Lewandowski enjoys at a juggernaut like Bayern. He was the man trusted to deliver, so the eye of the storm settled upon him. His first World Cup was the low point of his career, he says.

“The people were using this World Cup to punch me,” he recalls. “After the World Cup when we were on vacation, it wasn’t a vacation. That was so difficult a time. We wanted to come back home to see my family, but we get so many bad things in the media … not even about the football but my private things also, my club things. So this bad news, this bad communication, someone who wants to punch me uses this bad moment. That was a very, very huge challenge for us.

“If you have in the national team players like me, the expectations are very high,” he continues. “But alone I cannot do everything. I can help my teammates and my team to be better. But the team wins, not only one player.”

Michallik sympathizes.

“If you watch Poland games, I feel bad for him. I’ve seen or commentated most of the games and he never sees the ball. But it doesn’t matter because when it comes to big tournaments, it’s different here,” he says.

“These people are crazy in the moment,” Michallik adds. “They forget the logic. They understand that he can’t do it himself, but they still think of him as such a great player that he should be able to do it himself. And that’s why he has such a hard time, because you know the fandom turns into this hatred for a moment. And then a month later he’s at Bayern Munich, and those same people, he’s a god to them again.”

Lewandowski is far from the first player to star for a top-tier club while shouldering the burden for a second-tier national team (Lionel Messi’s situation doesn’t compare, as Argentina won two World Cups and 14 Copa América titles before he arrived. Their lofty expectations are more reasonable). But Lewandowski’s fame and formidable achievements, combined with Poland’s decline since the early ’80s, put him in a unique spot. Poland loves the game and remembers, faintly, how it felt to excel. Frustrated by the discrepancy between the intensity of that love and their lack of success, and longing for the glory they see Lewandowski acquiring in Munich, Polish fans and media are torn in two. The energy released is akin to splitting an atom.

But Lewandowski has willed his way through worse. The same fortitude he established as a teenager under duress, the same discipline and devotion that produced a career year at 31, will be channeled toward trying to finally deliver for his country. He does not yield.

“I believe the better days are coming, and the Polish team will be much better some time in the future. It’s not going to be immediate, and people shouldn’t expect that. You kick someone at the lowest point. That unfortunately seems to be part of the national psyche, and that’s what Lewandowski is on the receiving end of,” says Frankowski, who had an assist in Poland’s 1–1 friendly tie with Russia last week.

“He’s a really tough guy mentally. He’s at a level I cannot really believe. He can take these harsh words, and mostly he knows how much he gives the Polish national team,” Frankowski adds. “He’s a person who can work through these awful things, all the smack he gets from the fans, and somehow come to the right side of it even stronger mentally. And that’s the mark of a fantastic star player.”

Poland’s love for Lewandowski may sting and smother, but he loves it back anyway. Succeeding with Poland was a dream long before he ever imagined the Champions League or Bayern or Müller, and he’s going to continue to pursue it with his unique brand of intensity and commitment. Lewandowski has achieved everything at the club level. Poland is what remains. Making his mark in an international tournament and restoring pride to Polish football is what remains. The criticism and insults hurt, but pain has always been part of his process. It doesn't matter what they say. He'll choose the difficult way. His parents gave him to the world, but Lewandowski still hasn’t given up on delivering the world to Poland.

“To play for the national team is about honor and respect,” he says. “I’m not afraid of expectations or afraid of challenges. In my life I had so many situations where the situation could break me, and I never do this. It means, also, everything that’s going on is something for a reason. I don’t know exactly for what. But I try in every situation to make good things and try to learn something from this, to be more smart for the future.”

More Stories From Brian Straus:

0 Comments:

Post a Comment