Our critic sees cinema in a Sonics series, a retirement and a return. The real tearjerker, though, is about a boy, his dad and a ballgame.

There is something familiar about this. A sinister protagonist, rolling a cigar around in his mouth, holds a baseball bat and takes a couple short strokes, not ferociously but ominously, calculatedly, nodding his head as if engaged in secret thought. “Let’s see if all that trash talking starts when it’s zero-zero,” he says. Another short swing. It’s all totally gangster. “That’s the sign of a good man … (The words come out cigar-muffled) If you can talk s--- when it’s even score, or talk s--- when you’re behind …” More short swings that seem like brandishings. Deliberate head nods. Something is being plotted here.

And then it comes to you. The Untouchables. Whether or not Michael Jordan realizes it, he is channeling De Niro’s Al Capone. No, he will not bring the bat upon the head of a hapless pawn in some criminal empire. But, oh, good Lord, someone is about to suffer.

To read previous 'The Last Dance' recaps, click here.

It is testament to the depth and breadth of The Last Dance that in Sunday’s Episodes 7 and 8 we can in fact imagine ourselves staring at an ever-changing screen, images of movies and TV shows bouncing off our collective brainpan, literal chronology be damned. We go early to what could be an episode of Dateline. A highway at night, a red Lexus with a smashed window, a body discovered in a lonely South Carolina swamp, one bullet to the chest, the voice of Connie Chung linking—almost immediately—the murder of 56-year-old James Jordan to something juicier. “Jordan’s murder adds another bitter twist,” she intones in her best tabloid voice, “to the dark side of an All-American success story.”

We cut to The Rookie or Bull Durham, the carefree joy of the minor leagues, players chasing a teammate—in this case, the most famous athlete in the world—down a hallway.

We continue on to the Capone scene and then to a couple of afternoon movie specials that center on bullying. The first could cover Jordan’s incessant taunts and physical manhandling of a good-natured young forward named Scott Burrell, then in his fifth year as an NBA player but first as a Bull. “I tried to get [Burrell] to fight me,” rationalizes Jordan, “but in a good sense.” (Yes, he actually says that.) The other would carry the theme of Facing Down The Bully and would star Steve Kerr, who during a 1995 practice had the temerity to punch Jordan in the chest, receiving a return bash to the mouth. “Probably the best thing I ever did,” says Kerr, “was stand up for myself.” Once he did that, he became Jordan’s John Paxson of the second three-peat.

We make a literal movie stop, on the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank, Calif., where in the summer of 1995 Jordan is making Space Jam by day and organizing world-class pickup games at night, preparing for what will turn out to be a 72-win season.

We continue on to As the World Turns, accounts of Bill Cartwright and Scottie Pippen crying in the locker room after Scottie’s soap-opera moment, when he refused to enter the final seconds of Game 3 of the 1994 Eastern Conference playoffs because coach Phil Jackson had called a final-shot play not for him but for rookie Toni Kukoc. (One can only conclude that Pippen, normally a team player, feels worse when Kukoc connects to win the game.)

And of course we are taken on the obligatory excursion to Madison Square Garden for a showing of The King of New York, as Jordan double-nickels the Knicks in a 113-111 win, announcing to the world with 55 points that he is back … and that John Starks and Patrick Ewing may once again bring him his robe and slippers—and make it snappy.

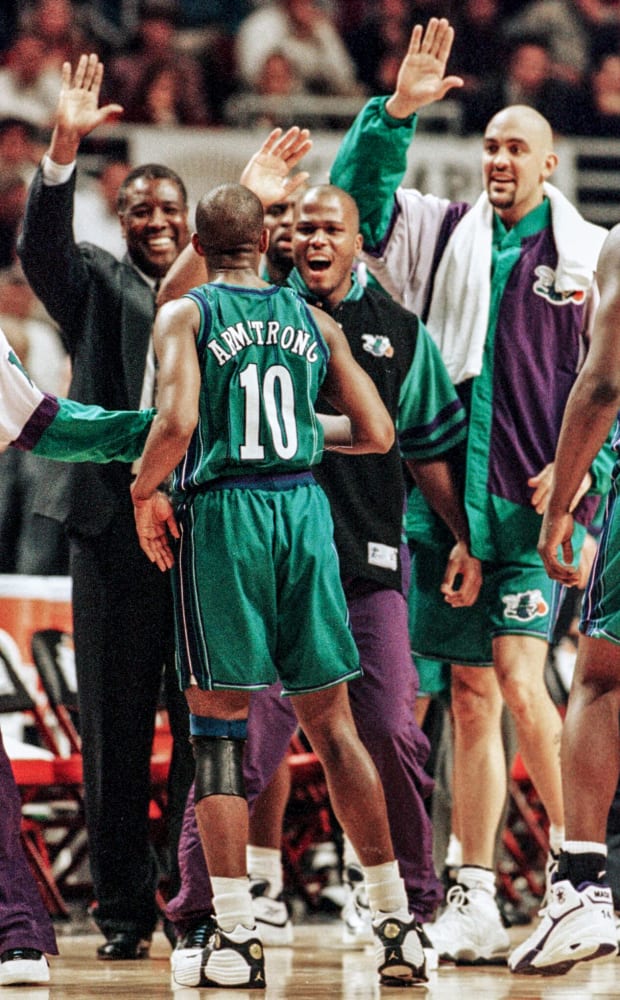

The patsy in Episode 8’s unforgettable bat-and-cigar scene is one Benjamin Roy Armstrong Jr., both an all-star dispenser of perspective in Jason Hehir’s epic-length documentary and a presence so earnest and likable that you can’t believe the B in B.J. doesn’t stand for “Boyish.” Armstrong’s transgression? As a member of the Hornets, the former Bull celebrates too joyously after punching above his weight in Charlotte’s 1998 Game 2 Eastern Conference playoff victory in Chicago. We see Armstrong rub Jordan off a screen and hit a key jumper, giving Charlotte the win by the oh-so-’90s score of 78-76. Michael, couldn’t you let the kid—who you so often kneecapped in practice—have a moment?

He could not, of course. Jordan smothers Armstrong at every opportunity and scores 27, 31 and 33 points in the final games in that Hornets series, settling us back into one of the documentary’s enduring themes: That MJ was quite often, as teammate Will Perdue bluntly puts it, an “a-hole” and a “jerk.” Free agents interested in the Bulls in the 1990s responded to this ad: Come for the championships. Stay for the abuse.

But that Michael-as-bully motif is leavened in Sunday night’s two hours by so many tears—a Brian’s Song level of tears… tears that flow not just from Pippen and Cartwright but from Jordan himself, as he tries to process playing basketball without the bright eyes of his father upon him. It’s such an emotional two hours that Jordan even gets overcome emotionally while discussing his own intensity. “The one thing about Michael Jordan,” says Michael Jordan at the very end of Episode 7, imagining the perspective of a teammate, “was that he never asked me to do something that he didn’t f---in’ do.” Pause. “Look, I don’t have to do this,” he continues, presumably speaking about sitting for the documentary and opening up about what drove him. “It is who I am. It’s how I played the game. It was my mentality. If you don’t want to play that way … don’t play that way.” Then he says, “Break,” tearing up in one of the doc’s most unforgettable moments, that rare time when Rare Air needed a timeout.

***

The murder of James Jordan, not surprisingly, hangs heavily over both of Sunday’s episodes. “If you knew Michael, you pretty much knew James,” says Tim Hallam, who as the Bulls’ long-time public relations director had the almost impossible task of choreographing Jordan’s daily press appearances. Owing partly to the father’s youthful appearance, Michael and James had a relationship that sometimes seemed more like brother-to-brother, but James was known around the Bulls as “Pops,” and his son, for one, never forgot the hierarchy.

In Episode 7, Michael speaks of a time in ninth grade when he was suspended three times (really?) for doing “mischievous stuff,” and his dad told him to forget about sports until he got it together. “From then it was tunnel vision,” says Jordan. “I never got in trouble from that point on.” There is, inescapably, a note of Shakespearian tragedy here—the intense father-son relationship, the brutal murder, the enduring grief—and, instead of an afternoon movie, we can turn to Henry IV, Part 1, as King Henry rues about the apparent course of his son’s life, seeing that “riot and dishonour stain the brow of my young Harry.” But Prince Hal eventually leaves behind the drunkard Falstaff and his wayward ways, and, though outnumbered, defeats the French at Agincourt, the prince’s equivalent of Madison Square Garden.

Jordan invokes the name of his father early during the Oct. 6, 1993 press conference when he announces his retirement from the game of basketball, as he so often put it. “I guess the biggest positive I can take out of my father not being here today,” Jordan says, “is that he saw my last basketball game.” (Actually: Between three more seasons with the Bulls and two with the Wizards, James could’ve seen 473 more games, playoffs included.)

It is hard to overstate the surreality of that October morning at the Berto Center in Chicago and what local broadcaster Mike Giangreco called “the ultimate press conference.” (But was it? Two years earlier Magic Johnson had announced to the world that he had HIV. That Los Angeles press conference also seemed kind of “ultimate.”) A carefully arranged seating chart, finalized by Jordan himself, planted him in the middle of a line of luminaries that included his wife, Juanita (nice to see her after six hours of doc with almost nary a female face, save for Michael’s mother, Deloris), coach Phil Jackson, owner Jerry Reinsdorf, commissioner David Stern, agent David Falk, general manager Jerry Krause and Curtis Polk, a Falk associate who handled much of Jordan’s business. Behind them stood a cadre of Jordan’s solemn-looking teammates, including Scottie Pippen, John Paxson and Scott Williams. (One wonders: What were they thinking? What the hell do we do now? Or More shots for us.)

“It looks like the Last Supper,” quips Giangreco. And in a way it was. (The Jordan retirement story, by the way, was broken by a dogged veteran NBA reporter named Mike Monroe, who at the time was working for The Denver Post. Monroe recently wrote about it for The Athletic.)

The revelations about Jordan’s gambling (see Episodes 5 and 6), the murder of his father and the shocking retirement presented a dilemma for journalists. How do you cover it all fairly? Are you obligated to mention that these things are possibly conjoined? Because, in truth, you have no idea. How do you make suggestions about links that may not be there, but that scream out to be mentioned? “It was not journalism’s finest hour,” says NBA public relations chief Brian McIntyre, as fair-minded a fellow as you can find, of the Jordan post-retirement coverage.

I’d like to think of myself as fair-minded, too, but I did bring up the unanswered questions in my Sports Illustrated cover story about that strange day. And my ears still burn when I remember Stern screaming at me after I asked, in a telephone call, about any possible connection between the murder and Michael’s gambling. “You should know better!” he said. “That is a disgraceful question.” But, as Stern knew, it was one on the minds of millions of people.

As I wrote in last week’s recap, I don’t believe there was a link between James Jordan’s death and his son’s gambling debts. There are still questions about the murder—here’s the best story I’ve seen about it—but the idea that Michael was responsible in any way has no credence, nor does the theory that Stern asked Jordan to take a hiatus from the NBA until those stories died down. This is all addressed most forcefully in The Last Dance by Mark Vancil, who covered the Bulls for the Chicago Sun-Times before joining Team Jordan as the president of Rare Air Media, Jordan’s communication company. (He’s now the managing partner of Williams Inference, a business intelligence concern.) “You’re telling me that David Stern, the ultimate capitalist, takes his number one player and his number one franchise,” says Vancil, incredulity dripping off of every word, “and unilaterally decides to lower the value of the rest of the league’s franchises by taking [Jordan] out—and the Bulls out, effectively—for some secret penalty? And no one ever finds out about it?” Vancil also breaks the news that Jordan confided in him a year earlier that he was thinking about retiring and giving baseball a go. I had not heard that before.

Though Jordan makes a public farewell to his father at that retirement press conference, James hardly disappears from The Last Dance. We’ll get back to Jordan’s time in Birmingham, but, even after Michael’s return to basketball, his father is always, well, around, never more than during the 1996 Finals against the SuperSonics. That was the season Jordan came back full-time, hell-bent on destruction, “frothing at the mouth,” in the words of Kerr.

Before that series, Jordan and Ahmad Rashad are having dinner at a Chicago restaurant when, according to Rashad, Sonics coach George Karl walks by without acknowledging them. “That’s all I needed,” says Jordan. Now, it’s doubtful that Karl, an avowed Jordan admirer, would see it that way—and anyway, who’s to say that, had Karl stopped for a word, Jordan wouldn’t have taken that as some kind of veiled insult? You hear that tone of voice he used when he said ‘Good luck’? I’m gonna kick their asses.

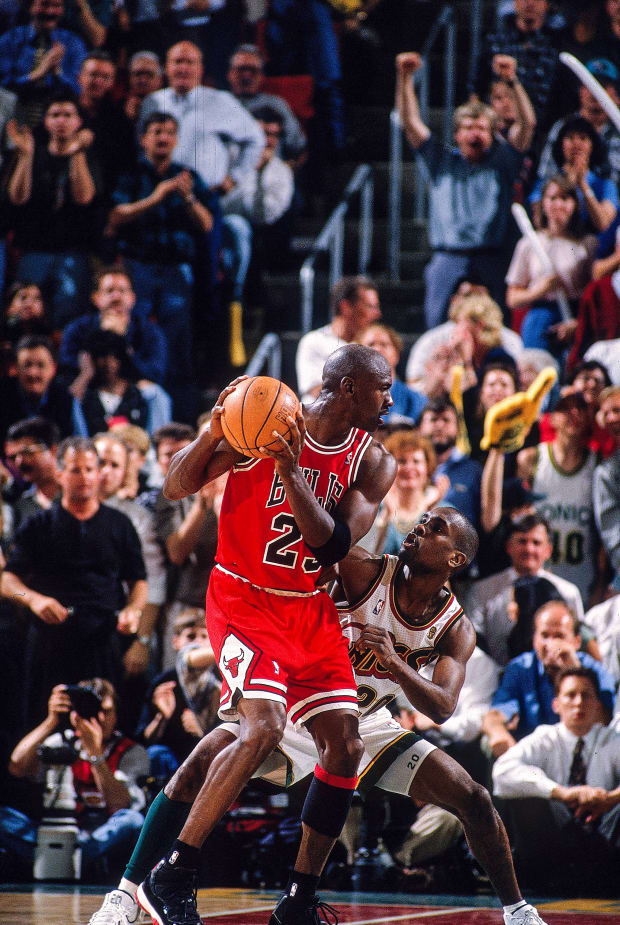

The Sonics series was expected to be a romp for the Bulls, and it began that way in the first three games. Seattle guard Gary Payton describes it downright anatomically: “First three games Michael ripped us. Ripped a hole in our ass really.” (Gotta hurt.) That’s when the Glove decided to cover Jordan, and he outplayed MJ in Games 4 and 5, sweep-saving Sonics victories in Seattle.

But Jordan suggests that all along he had a target date for when the Finals should most appropriately end: June 16. Father’s Day. “I had other things on my mind,” he says in the doc to explain away the anomaly of Games 4 and 5.

“A piece of Michael’s heart was missing,” says George Koehler, Jordan’s driver and confidante, who is very much a presence in these episodes. Deloris Jordan, too, confirms that her son’s mind was on James during that series. And there, at last, are Jordan’s kids, holding up a sign that reads: Happy Father’s Day Dad. From Jeffrey, Marcus and Jasmine.

Still, for all of Jordan’s controlling impulses, it’s hard to believe he would take the chance of blowing those games to set up a date to remember his dad. Subconsciously? Still unlikely. “I don’t think it was anything that was planned in advance,” says Sam Smith, who covered the Bulls for the Chicago Tribune. “Payton was the defensive player of the year that season, and, yes, it made a difference when George Karl—finally—put him on Michael.” Remember, too, that the Bulls had blown through everybody to that point, even in the postseason, and perhaps a two-game letdown, especially on an enemy court, was inevitable.

At any rate, back in Chicago Jordan outplays Payton in Game 6, Dennis Rodman grabs 19 rebounds (11 off the offensive glass) and the Bulls win by another one of those ’90s-era scores: 87-75. Certainly the postgame storyline is clear: Michael Wins it For His Dad. In one of the more amusing moments of the documentary, Hehir hands Jordan a laptop so he can listen to Payton explain how he held Jordan down in Games 4 and 5. Jordan laughs full-throatedly as he hears Payton’s voice and, suddenly, we cut to Goodfellas.

I’m funny how? Funny like I’m a clown? I a-muuuse you? Well, frankly, that’s how Michael played it, Gary. You a-muuused him. “The Glove,” Jordan says, his tone somehow denigrating the nickname as he hands back the laptop. “I had no problem with the Glove.”

What he did have a problem with that June evening in Chicago were his emotions, which got the better of him in a way we’ve never seen before. “I know he’s watching,” Jordan says in an oncourt interview with Rashad. “This is for Daddy.”

The Last Dance’s final scene from the ’96 championship series, the conclusion to one of the greatest single-season team performances in history, is Jordan writhing in agony on the locker room floor as, on the soundtrack, José González’s haunting cover of Massive Attack’s “Teardrop” plays softly in the background. Jordan is physically and emotionally spent, so tormented that even the camera crew, gold in its lens, quickly leaves him alone.

***

Jordan’s stint with the Birmingham Barons was a pivotal part of Sunday’s two hours, the solid middle infield if you will. Baseball was his refuge after the death of his father, and the fulcrum that relaunched him back into the NBA. O.K., so I’m not exactly The Natural. But how about if I remind you of where I am still the king? Could anyone leave a sport for 17 months, then come back at age 32 and be even better? Particularly when he had to undo the physical training he’d undergone for baseball? Well, we got an answer.

Sunday night’s two hours conclude back where they always do, in the 1997-98 Bulls season, ground zero for The Last Dance. But we must end this account here in Birmingham, the “Magic City,” so called because of its rapid growth in the early 20th century. And magic it was during the spring and summer of 1994, when Jordan was assigned to the Barons, the Double-A affiliate of the Chicago White Sox, which were owned by Reinsdorf. Jordan would’ve started in Class-A, or even the Rookie League, but press facilities simply could not have handled the crush that would be part of each and every one of the team-high 127 games he ended up playing.

After hours of now-familiar Bulls brass faces—Reinsdorf, Jackson, Krause—it is a pleasant diversion to hear from Mike Barnett, the Barons’ hitting coach back then, who reminds us that Jordan began his Double-A career with a 13-game hitting streak. It was after that Hobbsian start that Jordan, according to Barnett, “did not see a fastball in the strike zone for probably a month and a half.” A batting average that hovered in the .330’s eventually sunk below .200, and Jordan ended with a .202 mark to go with 51 RBIs, three home runs and 30 stolen bases.

As luck would have it for Jordan, his Barons manager was one Terry (Tito) Francona, who would later, you know, break the 86-year-curse of the Boston Red Sox with a World Series victory over the Cardinals. “[Jordan] wanted to know if we flew between cities,” Francona says in the doc. “I had to tell him that we rode buses. Birmingham to Orlando? Twelve hours.” Next thing you know, the Barons had themselves a real nice, 45-foot-long luxury ride, the leasing arranged by you-know-who. They called it the JordanCruiser.

Michael’s Minor League Adventure has aged rather well. I am not the one to evaluate the claims of Francona, Barnett and Reinsdorf that Jordan would have eventually reached the majors. (Certainly Jordan believes it.) But two knowledgeable writers have: Sports Illustrated’s Tom Verducci took a crack at it, and so did Steve Wulf, who wrote the infamous SI cover story that bore the headline BAG IT, MICHAEL! JORDAN AND THE WHITE SOX ARE EMBARRASSING BASEBALL. Both men conclude, You know what? Jordan might’ve had a chance. And, anyway, his time in the Magic City produced plenty of magical moments. He did not tarnish the game.

Still, the resistance to Jordan back then was real, and it was twofold. First, he was cutting the line, taking a spot that could’ve gone to someone else; secondly, he was using his fame and fortune to do something that all of us would love to do: live a fantasy, get a reboot. Hey, I always wanted to teach comparative literature, so why don’t I take over a class for a couple semesters at Columbia? … You know, I’ve thought about being a chef, so let me put on that apron from Brennan’s.

But, see, that’s not exactly what Jordan did. He decamped to a community college, not to Columbia. To a diner, not to Brennan’s. And in the process he became One of the Guys, a legit sweat-soaked minor leaguer who turned his hands into hamburger with multiple daily sessions in the batting cage.

Plus, no one could deny the legitimacy of Jordan’s dream—“one of the dreams I had when I was kid,” he says in the doc; a dream hatched long ago on the dirt fields of North Carolina; the dream of his father. Baseball was how James and Michael first related. Baseball was their first shared love. Millions of people can grasp that, particularly those of my age, a generation older than Jordan. Baseball was our fathers’ game, and so it was our game, too. And it remained, forever, our together game.

When I interviewed Jordan for my 2012 book Dream Team, I brought up the subject of his father gingerly. Given his fishbowl existence, I wondered if Jordan had taken the time back then—or ever, really—to adequately process the tragedy. Think about it: He wins a third championship in June. Confides to his father that he’s thinking about walking away. Hears the devastating news of his father’s murder in July and reads the suggestions that his gambling could be a contributing factor. Retires in a press conference that is beamed all over the world in October. Begins practicing for baseball by November, an exercise that many call foolish. Arrives at the spring training circus by March. And all of it comes under the most intense public scrutiny.

“I can’t imagine what you went through,” I said. “A brutal death. You were close. We later found out the autopsy was botched. And some people thought your gambling might have something to do with his death. You must’ve felt … violated. I always wondered if you think you’ve dealt with it, or if you ever felt you needed help. Or need help.”

“I dealt with it and I don’t need help,” Jordan snapped. “In my own way, I dealt with it. These guys—they had my father’s championship rings that I had given him, a lot of other personal stuff, a watch inscribed with ‘Love from Michael and Juanita.’ When they found out who they had killed, they videotaped the whole scene. The police tracked them because one of those idiots was showing the tape to his friends.”

“That’s what I mean,” I said. “That is incredibly hard. You know that one of the suspects was wearing—”

“—I know,” Jordan interrupted impatiently. “He was wearing a Michael Jordan T-shirt when he was arrested.” He was silent for a moment.

“So, how did you handle this whole thing?” I asked.

Jordan’s answer was emphatic. “It was baseball,” he said. “The Barons. There were a lot of lonely nights out there, just me and George [Koehler, his driver] on the road, talking. And I’d think about my father, and how he loved baseball, and how we always talked about it. I knew he was up there watching me, and that made him happy, and that made me happy, too.”

And so we come to the movie that plays over the James Jordan-Birmingham days—over Sunday’s entire two hours, really. Not a gangster flick or a bully movie, but the sometimes mawkish Field Of Dreams. “Hey, Dad,” Kevin Costner’s Ray Kinsella asks the ghost of his departed father, “wanna have a catch?” For all of his arrogance and searing competitiveness, for all of the times he ridiculed his teammates until “they got on the same level as me,” Jordan was—still is, to a degree—just a kid who wanted one more game of catch with Pops, the man who most clearly understood both his passion and his dream.

Jack McCallum covered Jordan for years as an SI senior writer and remains a special contributor to the magazine. The author of the New York Times bestseller Dream Team, he is the narrator of the upcoming podcast The Dream Team Tapes, due out May 18. Subscribe here.

More From SI.com

Inside the Making of The Last Dance

0 Comments:

Post a Comment